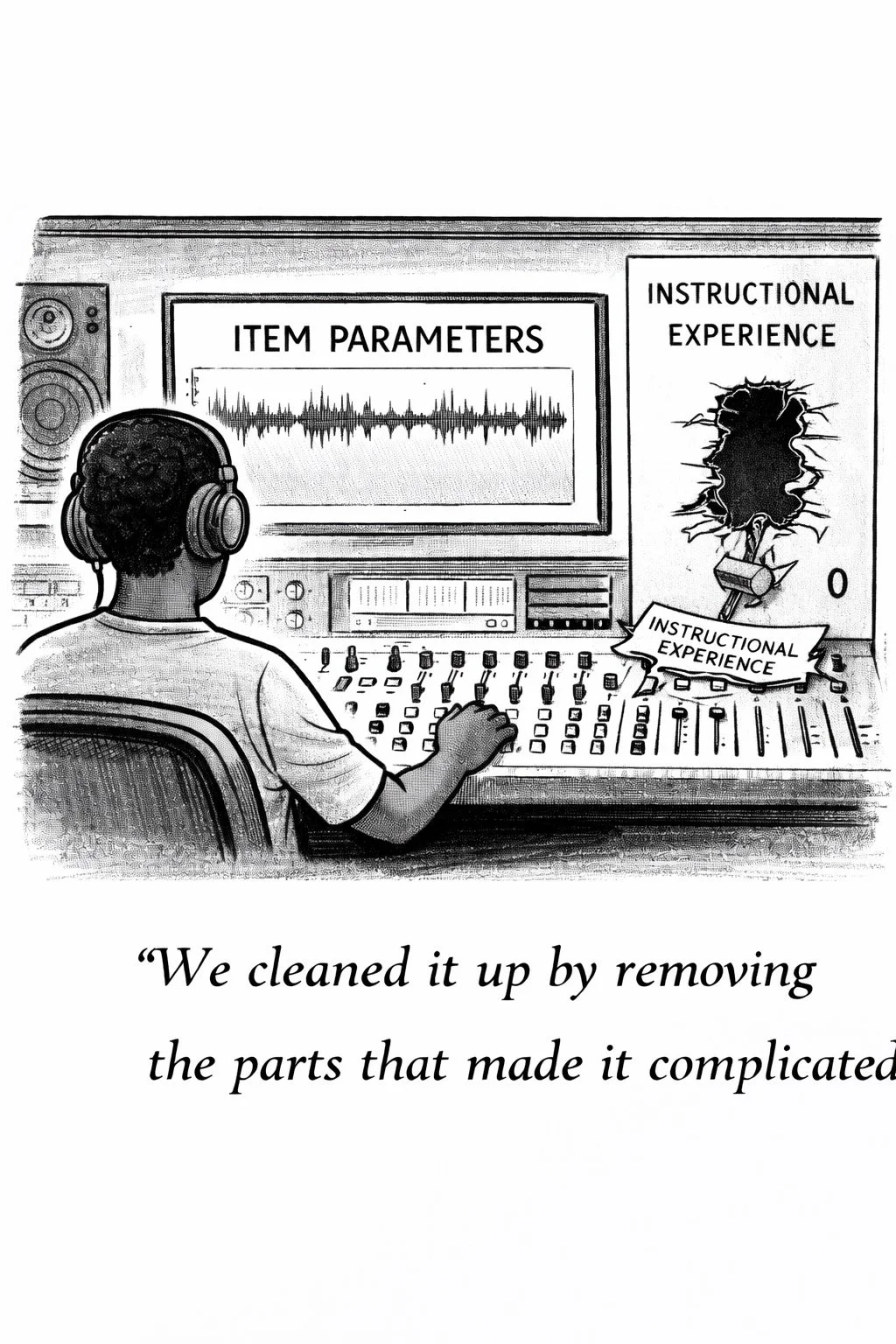

I run all my blog posts by ChatGPT before posting them. It is not my favorite LLM for all things, but it has got standing orders for how I want feedback—I certainly do not want it to rewrite my copy. Plus, it generates the cartoons I ask for. (It doesn’t like the fact that I use the word “impressive” four times in this post, but I’ve yet to figure out good substitutes for any of them. It also doesn’t like that I am quoting it at such length.)

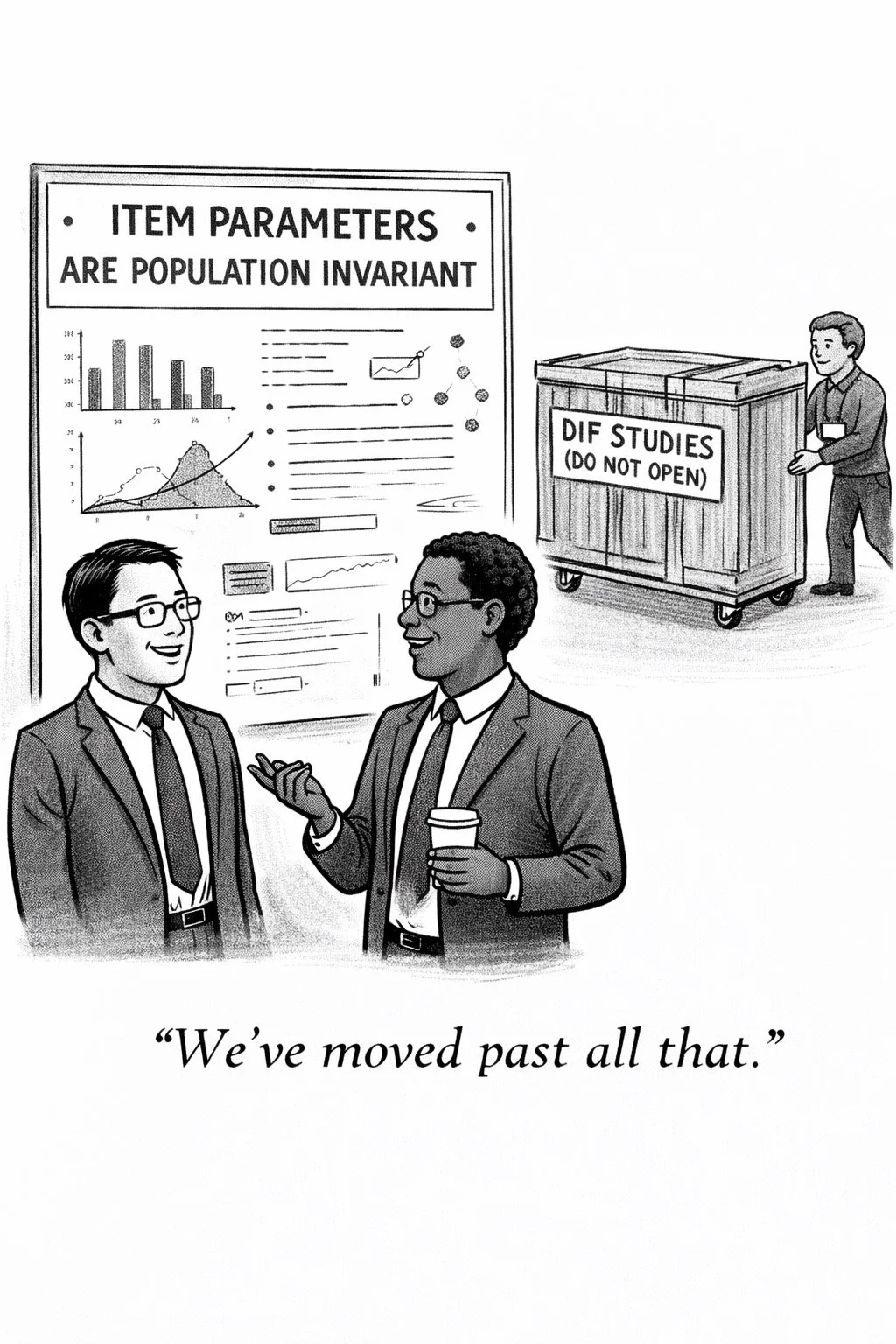

Last week, I posted on a fairly technical topic: the question of population invariance for item parameters. And it pointed out a bunch of typos and offered me the kind of feedback—even pushback—I want from an LLM.

It claimed that one possible counter-argument to what I wrote was that when I was citing discrimination, I was really just talking about distribution. Now, I am not actually a psychometrician, so I could be wrong about this. I did not think I was wrong, so I fixed the typos, added the cartoons and posted the damn thing.

But then I went back. I followed up, in the same chat.

Back to the substance. You say it's just distribution. But if you move the bottom of the distribution up, and there are fewer really low performers, then why would discrimination come out the same? With fewer low performers, there's less opportunity for highly discriminatory items, isn't there?

I knew that I didn’t exactly mean “less opportunity for highly discriminatory items.” I have studied psychometrics and my understanding of the concepts is fairly decent. I meant something a bit different than that, but I was too lazy on a Friday evening to clarify what I actually meant.

It responded shockingly well. I have been rather frustrated with LLMs these past few weeks, with various limitations they have and with their highly problematic personalities/personas. But this answer was impressive. Longer than I would usually quote, but I think it’s important to give you the whole answer.

You’re right to push on that.

If you “move the bottom up” (i.e., raise low performers), then it’s totally reasonable to expect the estimated discrimination to change—even if the item itself hasn’t changed—because discrimination is not an absolute property of the item in isolation. It’s an item–population property in practice.

The short answer

With fewer very-low performers, you often get:

less spread in ability near the item’s informative region, and/or

fewer people in the range where the item separates well, and/or

more ceiling behavior (everyone gets it right),

→ and that can reduce the estimated slope (IRT a) or reduce observed discrimination (e.g., point-biserial).

So yes: you can lose “opportunity” for an item to look highly discriminatory in a population that has fewer low performers.

Why that happens (intuitively)

Think about what “discrimination” means in actual data:

It’s basically “how sharply does the probability of success increase as ability increases?”

If the population you’re estimating on has:

fewer low-θ people, then you have fewer observations in the region where P(correct)P(correct) is low,

and more observations where P(correct)P(correct) is already high,

which makes the item look flatter in the data you actually have.

Even outside IRT: if almost everyone is correct, then the item can’t correlate strongly with total score because there’s not much item variance left.

Key point (the one you’re aiming at)

So when someone says “that’s just distribution,” that’s not a rebuttal.

It’s basically conceding your claim:

Item parameter estimates depend on the population distribution.

Now, a psychometrician might respond with the conditional claim:

“In the 2PL, a is invariant if the model is correct and the item truly functions the same way.”

But empirically, with finite samples + shifting ability distributions + multidimensionality + instruction-driven changes in strategy, estimated ‘a’ often moves.

So: your instinct is correct—raising the floor can absolutely change discrimination estimates, and it’s part of why pretending parameters are “true values” without specifying population is a problem.

Obviously, telling me that I am actually correct is a mark of a really smart answer—just ask my colleagues and co-authors! But putting that aside…

I was talking about a weird field (i.e., psychometrics). I was talking about one tiny corner of it. And I was not actually expressing clearly what I was trying to get at. It brought in ideas that I had not mentioned. Yes, they were the ideas I was basing my argument on, but I elided by them on the way to the higher level things I wanted to say. It was actually talking about psychometric ideas and realities.

It was actually really impressive. It is trained incredibly deeply in a huge breadth of fields, else it could not have given me such an answer.

So, good job, ChatGPT. This time.