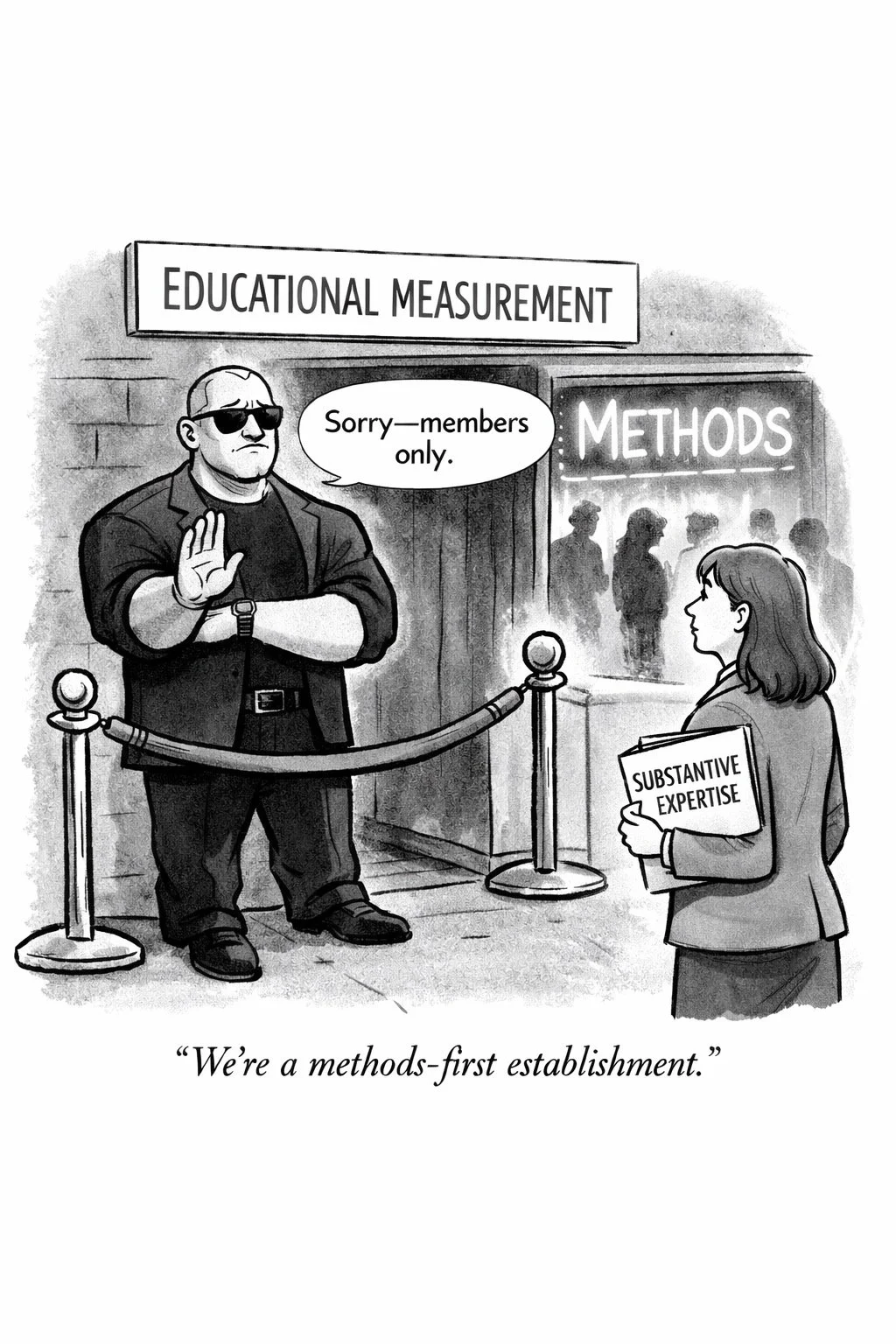

I saw a presentation on a using generative AI in educational measurementresearch project last week. Like so very very very many such projects, the mortar holding the whole thing together was disrespect for substantive expertise. That is, while this disrespect was not a building block of the project, all of building blocks would have fallen apart from each other if it weren't for the disrespect.

The project was about reading passages and determining their reading level—their suitability for different grade levels of students. I believe it seeks to build towards generation of high quality and appropriate passages for use on large scale assessments. This is an incredibly worthy goal, as stimulus quality and suitability is foundational to item and test quality. Moreover, finding or developing appropriate passages for large scale assessments is very time-consuming and expensive.

However, the research team did not include a single person with experience leveling passages. It did not include a single person with reading instruction experience. It did not include a single ELA content development professional (CDP). These omissions doomed the project to uselessness, just as so many other studies that lack substantive expertise are doomed to uselessness. Generative AI or psychometric methodological expertise are never going to be enough without substantive expertise.

This study provides a good illustration of many of the problems of relying on algorithms and ignoring substantive expertise, in part because its mortar is not at all unusual in our field.

* CDPs and reading teachers know that the standard algorithmic “readability” measures (e.g., Lexile, Flesch–Kincaid) do not produce results that are reliable or appropriate for students—often underestimating level, but sometimes overestimating. Because they have experience with the outputs of these algorithms in the context of their substantive work, they already know about the suitability and bias of the most easily available tools.

* CDPs and reading teachers know that idea complexity, emotional complexity and subject matter appropriateness are key determinants of grade level—factors that the standard algorithms entirely ignore. Methodologists (i.e., like psychometricians) working alone do not know what is relevant or not in a particular field.

* CDPs and reading teachers know that texts do not have a singular grade level, but rather each span a range of grades (or ages). More emotionally mature and skilled readers can handle texts that less mature and less skilled readers cannot. Therefore, the fact that texts may be appropriate for more than one grade does not mean that they cannot be quite clearly and recognizably different levels. (Consider one book that is generally appropriate for grades 3-5 and another that is generally appropriate for grades 5-7. The latter is clearly more demanding (i.e., a higher grade level text), even if both are suitable for 5th graders—albeit different 5th graders.). The difference will be immediately recognizable for those with substantive expertise. Outsiders will not even understand the appropriate scale or how instances interact with the scale.

* CDPs and reading teachers know that texts' reading level vary by geography, in part because different classrooms, schools, districts and even states have different views on what is appropriate at different grades. There are national aspirational ideas, such as at publishers and among leaders of national assessments. But I myself have taught in different high schools with very different ideas of what is appropriate for 9th graders. Amateurs and outsiders are unlikely to understand what is a rule and what is a guideline, what is a deep truth and what is merely a useful heuristic, what is clean theory and what is actual reality.

Perhaps the worst thing about this study was that when I asked one of the team members—the leader?—whether they included any reading teachers or ELA CDPs on the team, she said that it is hard to find such expertise. This is patently false. In fact, I can think of no type of expertise that is easier to find in this country than reading instructors. I believe that you can ask the vast majority of adults in this country where a nearby elementary, middle or high school is (i.e., a school full of reading instructors), and they could tell you. This is surely easier than finding an architect, pilates instructor, sandwich engineer, psychometrician, project manager, sanitation worker, plumber or nurse. No, the problem was not that they could not find any ELA CDPs or reading teachers. No, the problem is that they did not even think to try.

This kind of disrespect for substantive content expertise is not at all unique to this study. Heck, in educational measurement research it is the norm. But without substantive expertise on the research team, there is no way for researchers to know whether what they are seeing is typical or an outlier. There is no way to know whether their simplifying assumptions are too much to yield any useful findings at all. There is no way for them to make sense of their inputs or outputs. With substantive experts on the research team, they can be highly capable collaborations of different expertises that produce meaningful learning. Without substantive experts on the research team, they are merely collections of outsiders making blind guesses without even understanding the questions.

Our assessments are not going to get better while disrespect for substantive expertise remains the mortar of educational measurement research. When you build studies on that foundation, you don’t just miss important details—you lose the ability to recognize what matters, to interpret what you observe, and to know when your conclusions are nonsense. And if generative AI becomes the tool we use to replace the experts we refuse to respect, we will only get faster at producing invalid work, rather than better at producing good work. If we care at all about validity—the degree to which theory and evidence support the proposed uses of tests—we must do better.