First off, there is no defense for bad multiple choice (MC) items. The floor on the usefulness of MC items is incredibly low. I am only talking about high quality MC items—which are incredibly hard to write. Admittedly, most MC items are quite bad.

(For example, do not be confused by the psychometric demand that multiple choice items be quick to answer. That is not inherent to the MC item. They could require quite a bit of work and thinking, if only our psychometrics overlords were not distracted by alpha. The shallowness of most MC items is a product of that demand for speed, rather than anything intrinsic to the MC item.)

Second, I am a former high school English teacher. That’s about teaching students to develop their ideas and teaching them about the value of the writing process for doing it. It is about deeply understanding relatively complex texts—and other human beings. It is about argument and evidence and audience awareness. It is about listening, dissecting and analyzing. So, multiple choice items are really hard for me to love; I have seen so many shallow and otherwise bad MC items that it has been a journey for me to understand their value.

And yet…I think that good multiple choice items can be quite useful. Perhaps even more importantly, learning to write good multiple choice items is an incredibly powerful exercise for anyone writing any type of assessment.

Obviously this (new school) begs the question of a what a high quality MC item even is. Though there are many many content and cognition traits to a good multiple choice item, I’ll limit the discussion here to just five of them:

* A definitively correct key.

* A set of definitively incorrect distractors.

* Each distractor must be plausible.

* The set of distractors must capture the most common mistakes that test takers are likely to make.

* The stem, the key and the distractors must all be aligned to the learning goal (e.g., state learning standard).

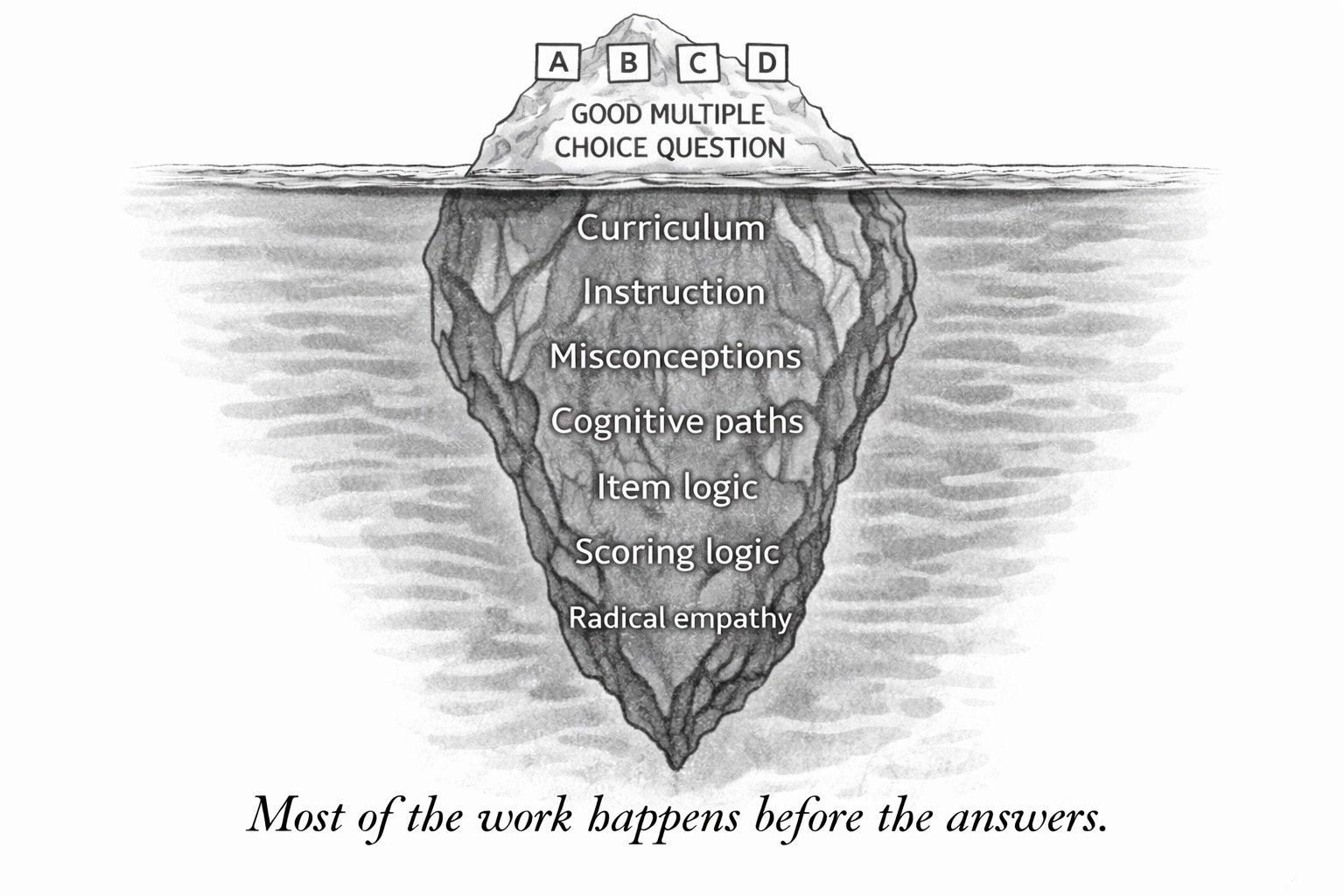

Therefore, writing a high quality MC item requires understanding the learning goal. Obviously. Duh. Furthermore, it requires understanding how students progress with that goal. That’s the only way to know what their most common mistakes are likely to be. All of that is dependent upon knowing how they think—very much a product of the curriculum, instruction and pedagogy they have experienced—at various stages of learning and understanding that learning goal.

Therefore, writing high quality MC items requires deep knowledge and understanding of how lessons are taught—the range of curriculum, pedagogy and examples that students might experience. Some approaches to teaching a given learning goal are going to focus on some type of things and avoiding some kinds of mistakes. Others will prioritize different things or mistakes. Which metaphor the teachers uses when explaining a scientific concept can invite different misconceptions. And different efforts to clarify the meaning and value of the metaphor will make some mistakes less likely than others. Writing good MC items requires thinking deeply about how students might respond to different instructional approaches.

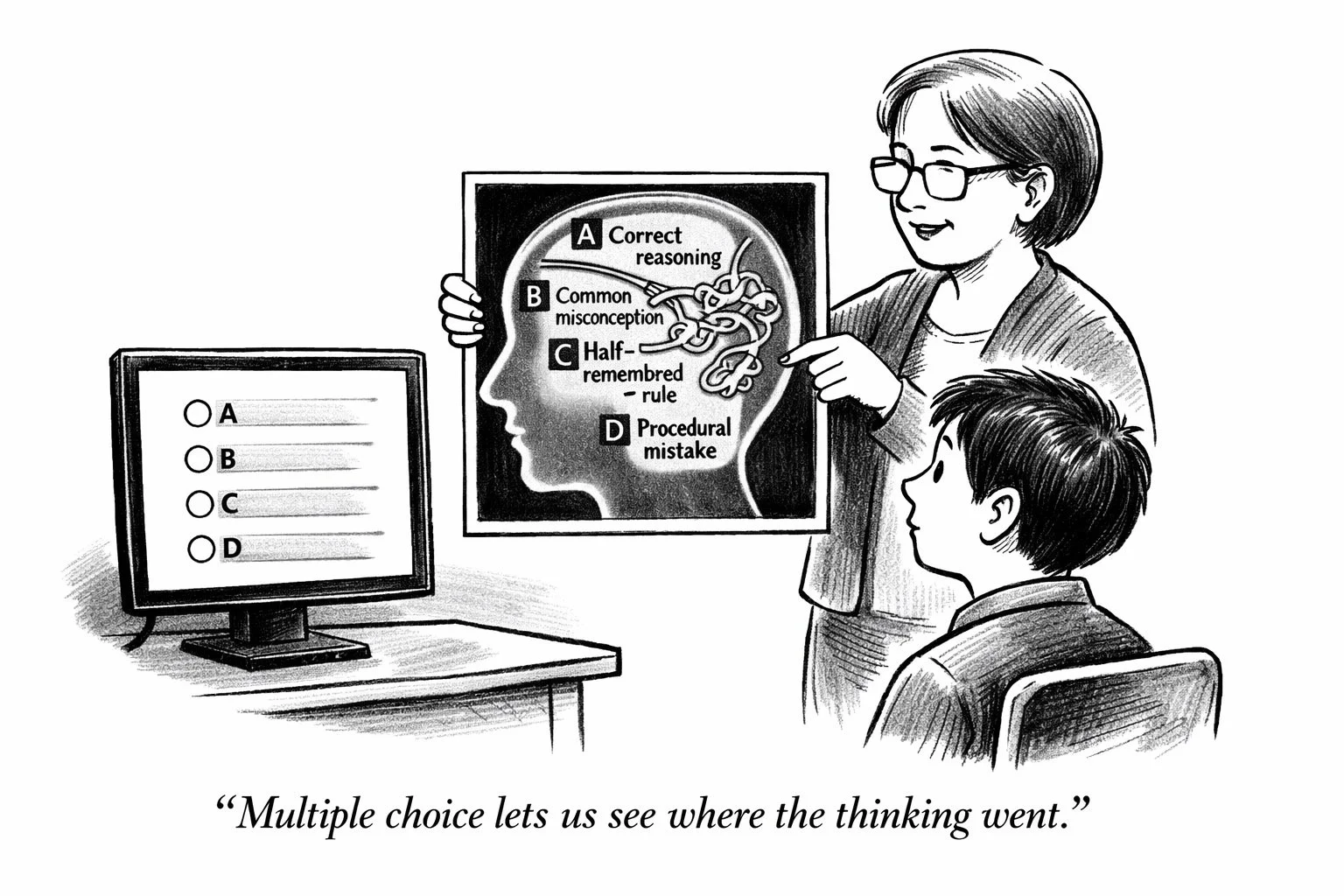

Good MC items require the most careful attention to the knowledge and skills required to solve the item, which includes mindfulness of alternative routes to successful responses. Again, this leans on deep understanding of students’ cognitive processes—which (again) is strongly influenced by the instruction they have received. It requires student-centered thinking that acknowledges the range of students who might encounter the item. It is not simply about imagining the different responses that students might give, but rather about understanding the different cognitive paths they might take, the various correct and mistaken steps along those different paths. And then, in order to develop a good MC item, crafting answer options that reveal those paths to teachers (or other concerned parties).

(We call this vital understanding of the various cognitive paths that the range of test takers might take in response to an item radical empathy. It is a pillar practice of content development professionals’ work, perhaps its most rigorous and demanding aspect. It is easily recognized by high quality teachers, but is quite foreign to most other disciplines.)

The defining characteristic of MC items is that they list a set of possible responses. This should not make them easy, as whatever misconceptions students bring to item should find a welcoming distractor that reveals it. An advantage of this approach is that it signals to students that non-aligned mistakes (i.e., misconceptions grounded in some other lesson) are mistakes, and they should try again. Therefore, the set of answer options act as a filter to capture just the relevant misconceptions and mistakes—making them more apparent for teachers or interested parties.

Well, sure. Bad constructed response items are bad. It is not really fair for me to compare high quality MC items to low quality constructed response items. But my point is that if the item developer is clear on what they are targeting and what both confirming and disconfirming evidence might look like, MC items are not always inferior to constructed response items—especially if they can provide actionable information faster and cheaper than constructed response items. (That is, scoring and reporting is faster and cheaper.)

The difference is that good MC items require all of this rigorous thinking to be done up front. They demand real investment in thinking through the range of what students might do—the cognitive paths they might take in response to the stimulus and question. Yes, scoring is easy and fast, but is only because of the amount of incredibly demanding work done up front. Constructed response items that put off that thinking until it is time to score them can be just as bad at providing insight—often what teachers (like myself) stick themselves with.

Obviously, not all learning goals are amenable to multiple choice items. Certainly, the objectives of high school writing lessons are a bad fit. There are real limits within the topic of research design and other aspects of lab science on the usefulness of MC items. But if we can focus on crafting good MC items and abandoning the counterproductive demands of psychometricians, good MC items can be invaluable—both to summative and formative assessment.